Evan Rosa: This is For the Life of the World, a podcast about seeking and living a life worthy of our humanity. I’m Evan Rosa—today we’re bringing you a midweek episode of the show featuring Ryan McAnnally-Linz, Associate Director of the Yale Center for Faith and Culture, and co-author with Miroslav Volf of “Public Faith in Action: How to Think Critically, Engage Wisely, and Vote with Integrity”—he also helped develop and continues to co-teach the popular Life Worth Living seminar for Yale undergrads.

We’ll have another episode on coming on Saturday, with Miroslav Volf exploring what it means to conquer fear, juxtaposing Jesus’ repeated teaching to “Fear Not” with his Gethsemane struggle and prayer to “Remove this cup from me.” A fitting reflection for Holy Week and Easter weekend in the time of COVID-19.Over to Ryan McAnnally-Linz with a reflection on human vulnerability, the response of Stoicism, and the call to Christian love.

Ryan McAnnally-Linz: In his book Homo Deus, Yuval Noah Harari suggests that, once basic human survival is secured by overcoming famine, war, and pandemics, the natural progression of the human species will be to seek a god-like existence of immortal happiness. But as our distressing under-preparedness for a pandemic has shown, we still haven’t conquered these basics, leaving us feeling vulnerable and insecure.

Indeed, this global crisis has unveiled a whole host of purported securities as frauds—everything from the financial “securities” that underwrite the crashing global market, to the physical security we get from a health care system now verging on catastrophic overload. In doing so, the pandemic challenges those of us who are used to security and control—and I count myself among them—to recognize the inescapability of vulnerability in a new, deeper, and profoundly troubling way.

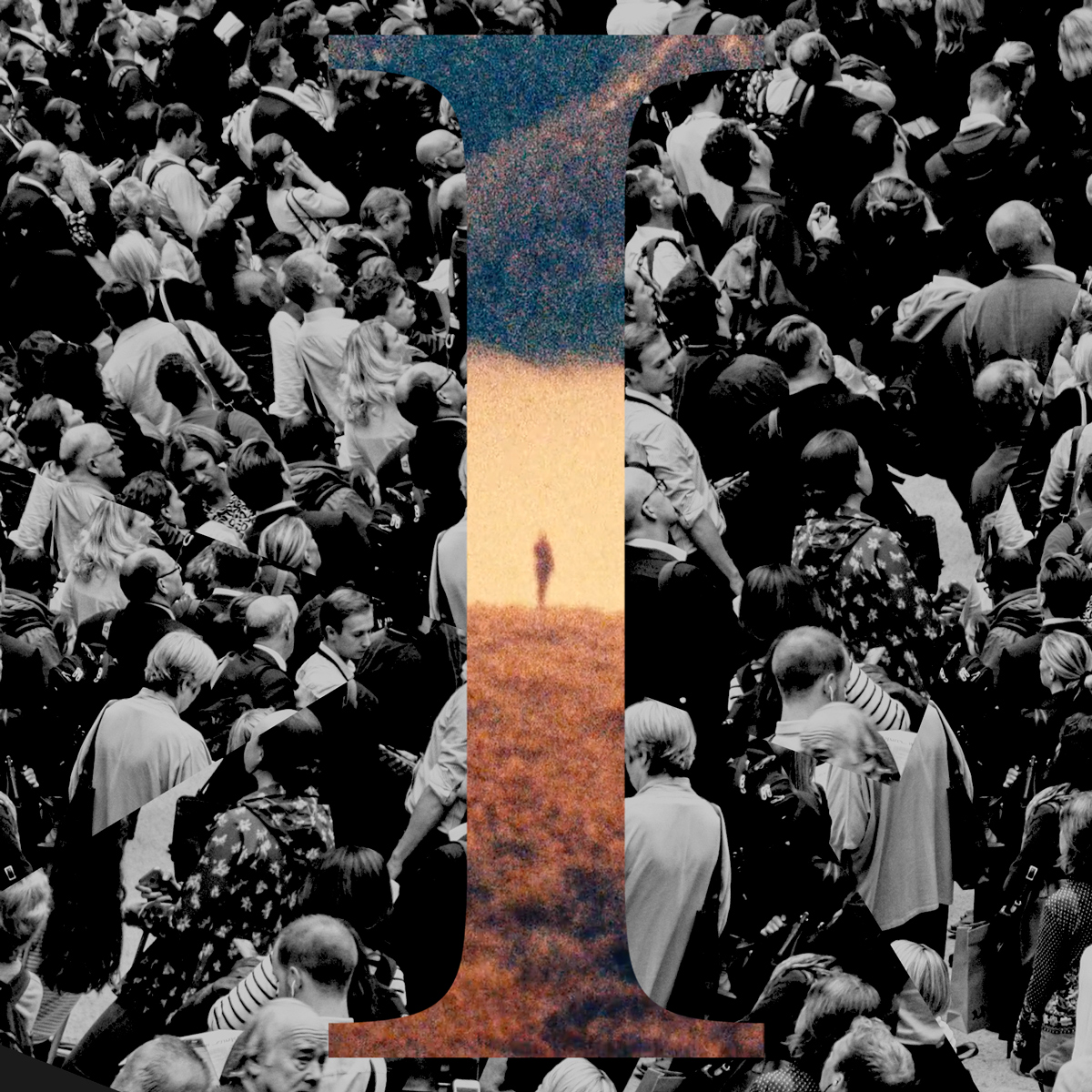

The fact is: Our lives are always shaped and altered, sometimes even shattered, by forces outside our control.

The sudden realization of our own vulnerability that many of us are now experiencing is far from pleasant. It is liable, therefore, to spark attempts to overpower or outwit our vulnerable position in the world. Taking the brute force approach, we indulge the urge to build the best possible fortresses. We acknowledge that we cannot get rid of vulnerability altogether, but also note, rightly, that we can reduce it. And so we try to secure our individual or collective lives as best we can. We build higher walls, stock fuller pantries, fill a war chest with toilet paper and hand sanitizer, buy better insurance, and vow to keep a safe distance from others at all times. There are, I would note, widespread reports of gun sales spiking across the U.S. as the coronavirus spreads.

And yet, when pressed, we might be forced to acknowledge that fortresses, even the best of them, aren’t secure enough. Every fortress falls eventually, after all. Every stockpile eventually runs out. So we can be tempted to look for an even more radical response to our vulnerability.

Enter Stoicism, an ancient philosophy that has been experiencing a renaissance in recent years, and may have particular appeal in our current situation. The Stoics saw that no amount of external resources could ever insulate us from misfortune. That means that if a good life depended on anything outside the individual person (“outside the soul,” they would say), it would be inherently insecure and fragile. But whatever the good life is, the Stoics thought, it must be something that’s in a person’s own hands. It must be securable.

The idea they settled on was that virtue, excellent rational agency, is the whole of the good life. Our investments in external things hinder our pursuit of virtue and thus keep us from the good life. Consequently, the Stoics came up with various techniques, or therapies, for overcoming our tendency to be disturbed by external events, to quell all our irrational responses, to learn not to let misfortune disturb the tranquility of a rational soul by learning not to see it, strictly speaking, as misfortune at all.

Following the Stoics, we might find ourselves responding to COVID-19 by training ourselves not to be internally affected by the turmoil around us. This training could look like denying the severity of the crisis or teaching ourselves to see it as overblown political theater. It could look like withdrawing our emotional investment in relationships with others, or like focused breathing and meditating the stress away. At its most extreme, it could look like the Stoic practice of memento mori, reflecting on the eventuality of our own deaths to dull the fear of their arrival.

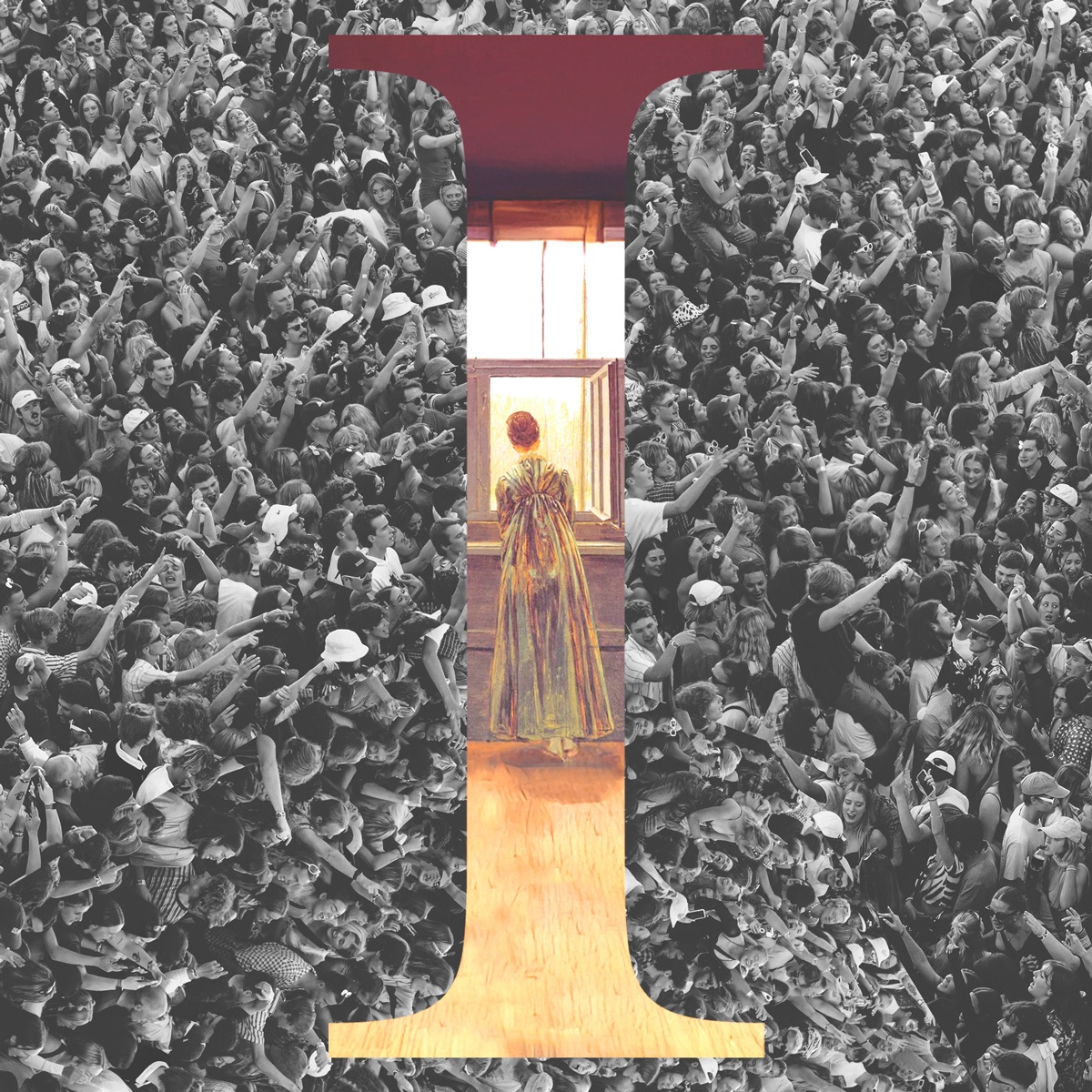

Fortress building and Stoic detachment are tempting in times like these. But they are fundamental failures to acknowledge the full scope and depth of our relationships to each other. Human beings are made for communion, for loving interchange and connection. Stoicism denies the profound goodness of our material and emotional relationships with others. It is social distancing of the soul—which, from a Christian perspective, would be a quite fitting description of hell. In search of security, Stoicism severs our mutual attachments and thereby dismembers us, for each of us in fact lives only in and with others—“individually we are members one of another” the apostle Paul says in Romans 12. Fortress building, for its part, is simply flagrant injustice and denial of responsibility. It is a refusal to be in this together. It lies and says that our fellow humans are not our neighbors, and therefore it amounts to wishing our neighbors dead. It is the “war of each against all” that Thomas Hobbes imagined (wrongly) as our state of nature.

When faced with the reality of our vulnerability, we have to do better than building fortresses or retreating into ourselves. But that’s not all that needs to be said, because it would be easy to go overboard. The trick is not to overcompensate for our own and our culture’s aversion to vulnerability by uncritically valorizing it, by saying, for example, that now is a time to embrace our vulnerability and the inherent riskiness of life.

Vulnerability per se is neither good nor bad. It is simply a fact of our lives as finite creatures. We depend on other creatures, large ones like the sun in the sky and small ones like the bacteria in our guts, for our very lives, and therefore we are vulnerable to harm. But that does not mean that it’s good to be subject to harm, much less to actually be harmed. It’s not. There are, therefore, forms of vulnerability that we ought to seek to mitigate, for our neighbors, but also for ourselves. The social distancing we’re currently practicing aims at doing just that. It is not good to be more vulnerable to a rampaging virus, so we ought to do our best to reduce that vulnerability. But that doesn’t mean an everyone-for-themselves rush to the fortresses.

The key is to see that one person’s vulnerability gives rise to responsibilities on the part of others. This dynamic is easiest to see at its most extreme: the acute vulnerability of infants. Precisely because infants are so subject to harm and so vulnerable, we recognize that we have intense responsibilities toward them. This same relationship of one’s vulnerability to another’s responsibility applies in other contexts too, including the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus doesn’t affect everyone equally. Some, especially the old and the immune-compromised, are especially threatened. And so we have particular responsibilities toward them.

In most circumstances, when vulnerability gives rise to responsibility, it calls us into physically closer relationships. I remember drawing near, again and again, to my infant daughter to feed her, comfort her, give her warmth. That call to nearness is the promise of vulnerability. The good that vulnerability points us to is love, caring communion and intimate connection. The situation with COVID-19 is strangely different, and yet the fundamental good at stake is the same. Health-care workers are, indeed, drawing near to the afflicted, at much risk to themselves. But the vast vulnerability to this virus asks something different from the rest of us. It asks that we keep our distance. Self-isolation is precisely the mode that communion takes under the conditions of this pandemic.

In what is probably his most famous parable, Jesus tells the story of a man who is beaten by robbers on the road between Jerusalem and Jericho. Three devout religious leaders see the man lying beside the road and pass by on the other side. An ethnic and religious “other,” in contrast, stops and cares for the wounded man at great cost to himself. It is a poignant expression of the call to take up responsibility for those whose vulnerability has left them harmed and in need.

We all are vulnerable, subject to forces that we cannot determine or control, apt to find ourselves in the state of that beaten man by the side of the road. That fact is all too clear right now. What’s of vital importance is that we neither flee from it, nor embrace it cavalierly, but face it and address it in love for our neighbors. Even the strange kind of love that, unlike the Samaritan in Jesus’s parable, keeps a minimum of six feet distance on the other side of the road.

Evan Rosa: Thanks for listening friends. Take care of yourselves, take care of each other. We’ll be back with another episode this Saturday.For the Life of the World is a production of the Yale Center for Faith & Culture at Yale Divinity School. This episode featured Ryan McAnnally-Linz, Associate Director of the Yale Center for Faith & Culture. You can follow him on Twitter @RJMLinz. I’m Evan Rosa, and I edited and produced this show. For more information, visit us online at faith.yale.edu, and subscribe to the show wherever you listen to podcasts. If you’re looking for a way to support us, that could be as simple as telling a friend, leaving a rating and review in Apple Podcasts, or sharing the show in your social feeds. Thanks for listening, and we’ll be back next week.